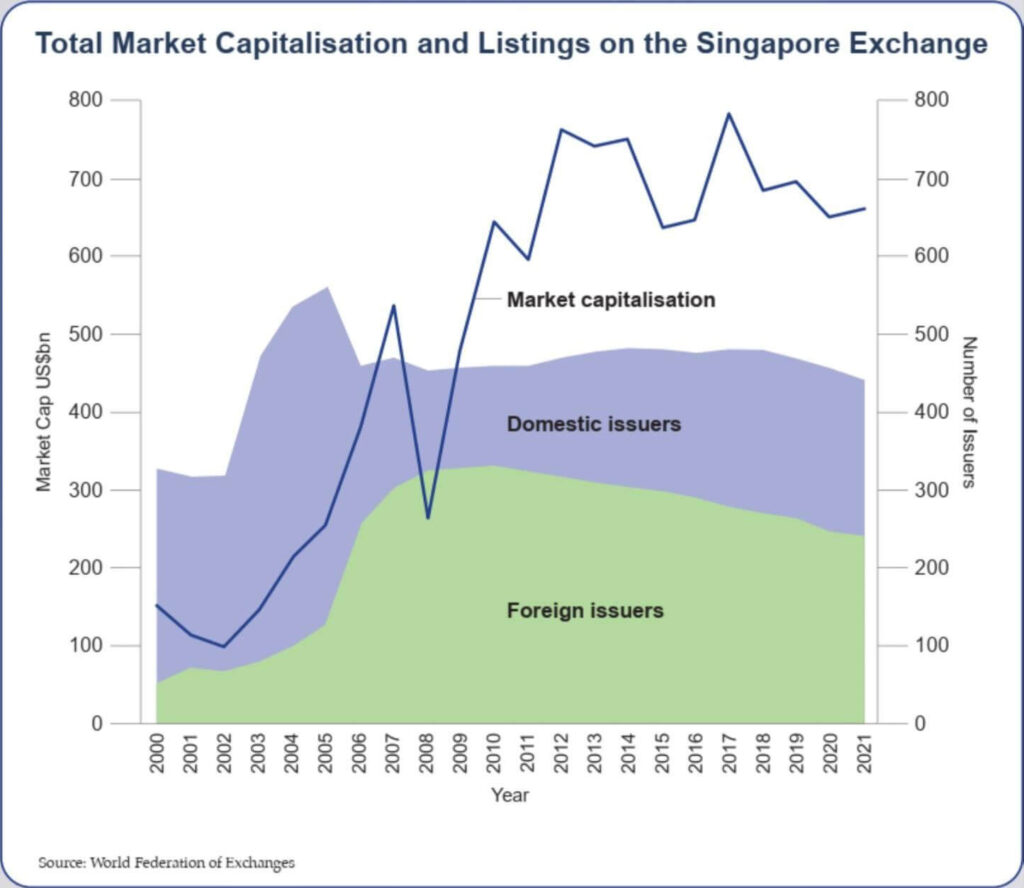

In November 2000, the Singapore Exchange (SGX) became the third stock exchange in the Asia Pacific to be listed, after Australia and Hong Kong. As of December 2021, there were 673 listings on SGX (including 27 secondary listings), with a total market capitalisation of US$663 billion (S$914 billion).

The total market capitalisation is now more than four times, and the number of listings is nearly 80 per cent higher than in 2000. However, this is still off the peak of US$790 billion at the end of 2017, and the 778 listings in 2010. (See box, “Total Market Capitalisation and Listings on the Singapore Exchange”).

Several aspects of SGX development bear highlighting in discussing corporate governance reforms: local vs foreign issuers, Catalist and REITs (real estate investment trusts).

Foreign vs local issuers

Over the years, there have been significant changes in the profile of listed issuers. The first major bump in listings occurred in 2003, with more than 150 new issuers (mainly domestic).

A big increase in foreign issuers took place in 2006, when the numbers more than doubled.

This was due to the “S-chip” wave, with an influx of China companies.

The number of foreign listings continued to increase after 2006 but at a slower rate, reaching its peak at the end of 2010. Foreign issuers have since declined by more than a quarter.

Between 2008 and 2011, the percentage of foreign listings made up more than 40 per cent of all listings, with those from China constituting about half. Foreign listings now constitute around 30 per cent of the total number of issuers.

Today, China listings number just 70, less than half their peak, making up about one-third of all foreign listings.

Catalist

The establishment of the second board, Catalist, came 20 years after the original second board, SESDAQ, was started in 1987. Catalist operates on a sponsor-based regime modelled after AIM (Alternative Investment Market) in London. It is intended for growth companies with no or minimal financial or operating history. Thus, the admission requirements and processes, ongoing oversight, and continuing listing requirements apply differently between Mainboard and Catalist companies.

Over the past 10 years, Catalist listings have nearly doubled from 17 per cent to a third of all listings today. Catalist listings generally do not attract significant institutional investor following.

REITS

Since the first real estate investment trust (REIT) in 2002, SGX has become a vibrant market for such issuers, and is now ranked third by market capitalisation in Asia-Pacific, after Japan and Australia.

There are now more than 50 listed REITs, business trusts and stapled trusts. Additional rules and oversight by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) apply to this sector.

Corporate governance reforms

Following the Asian financial crisis of 1997 and 1998, when weaknesses in corporate governance and disclosures were identified as a key contributing factor, Singapore embarked on major reviews of company law and the regulatory framework, corporate governance and disclosure standards. These reviews were also intended to support the move from a merit-based approach to a disclosure-based approach to regulation.

A key aspect of the reforms was the issuance of a Code of Corporate Governance in 2001 to complement the SGX Listing Rules. The box, “The Code of Corporate Governance”, sets out the key provisions and revisions to the Code over the years.

The Code operates on a “comply or explain” basis where issuers have to comply with the Code or explain why they have not. The most recent edition of the Code in 2018 sought to significantly strengthen the “comply or explain” approach by moving certain practices to the Listing Rules (which is mandatory for listed companies to follow), and requiring that issuers must comply with the principles of the Code. Variations from provisions are acceptable only if consistent with the intent of the principles.

Corporate governance implementation

How has the implementation of the Code and corporate governance practices fared over the years?

In 2006, MAS and SGX commissioned a review of the implementation of corporate governance practices in Singapore. A 136-page report released in 2007 contained eight sets of recommendations relating to:

(1) Improving the implementation of the “comply or explain” requirement.

(2) Independence, effectiveness and pool of IDs.

(3) Remuneration disclosures and policies.

(4) Audit committee.

(5) Internal controls and risk management.

(6) Training of directors.

(7) Exemption from SGX listing requirements (for secondary listings).

(8) Institutional shareholder activism.

When we review these eight areas against the situation today, those that have made the least progress are arguably those relating to:

(1) Implementation of “comply or explain”.

(2) Independence, effectiveness and pool of IDs.

(3) Remuneration disclosures and policies.

(4) Institutional shareholder activism.

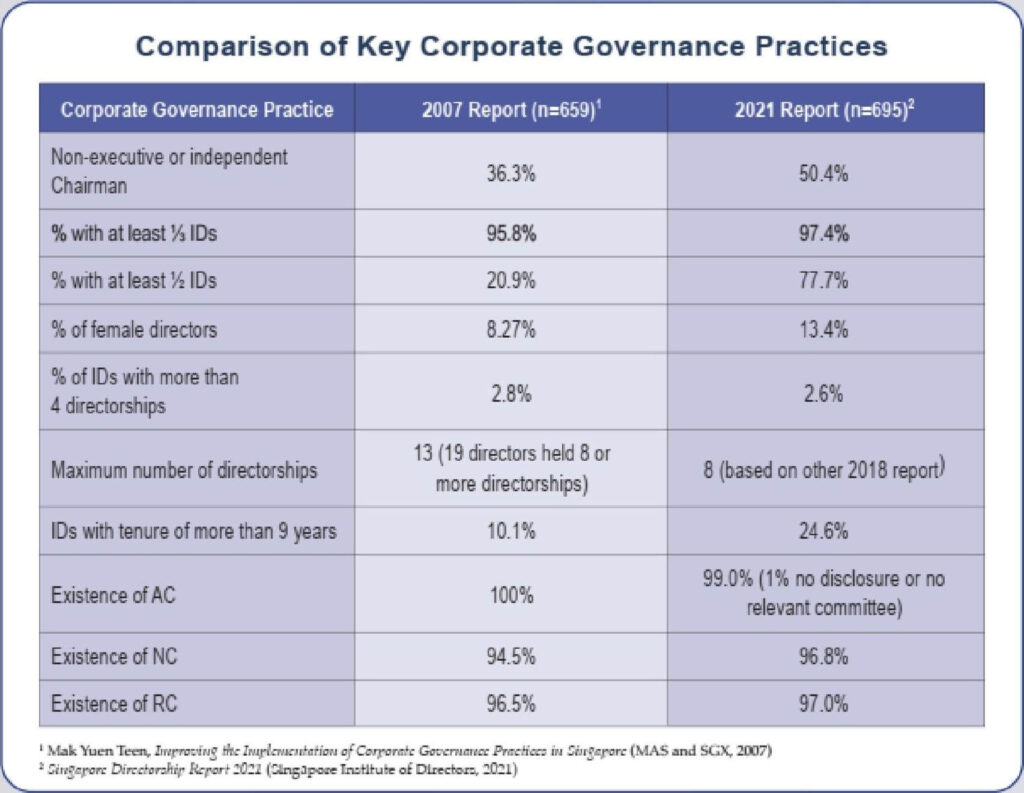

But, in terms of the adoption of “best practices” and reduction of certain questionable practices, there has been progress, at least on the surface. See the box, “Comparison of Key Corporate Governance Practices” which contrasts the key corporate governance practices documented in the 2007 report (data was based on 2005/2006 annual reports of companies) with the same practices extracted from the SID’s Singapore Directorship Report 2021 (data was based on the annual reports of companies for years ending up to 31 December 2020).

Nearly all practices have improved. However, a notable exception is the percentage of IDs with tenure exceeding nine years. It is not surprising that there were relatively fewer IDs with long tenures found in the 2007 study, as the recommendation for having IDs was introduced only in the 2001 Code. Since then, the situation has deteriorated with nearly a quarter of IDs having tenures exceeding nine years. However, with SGX listing rules now prohibiting an ID from serving beyond nine years unless they are approved by a two-tier vote of shareholders, one would expect the percentage of such long-serving IDs to decline – although certain limitations of the two-tier vote implemented here in Singapore are starting to show (See page 26, “Long Serving IDs and the Nine-Year Rule”).

Corporate governance ratings

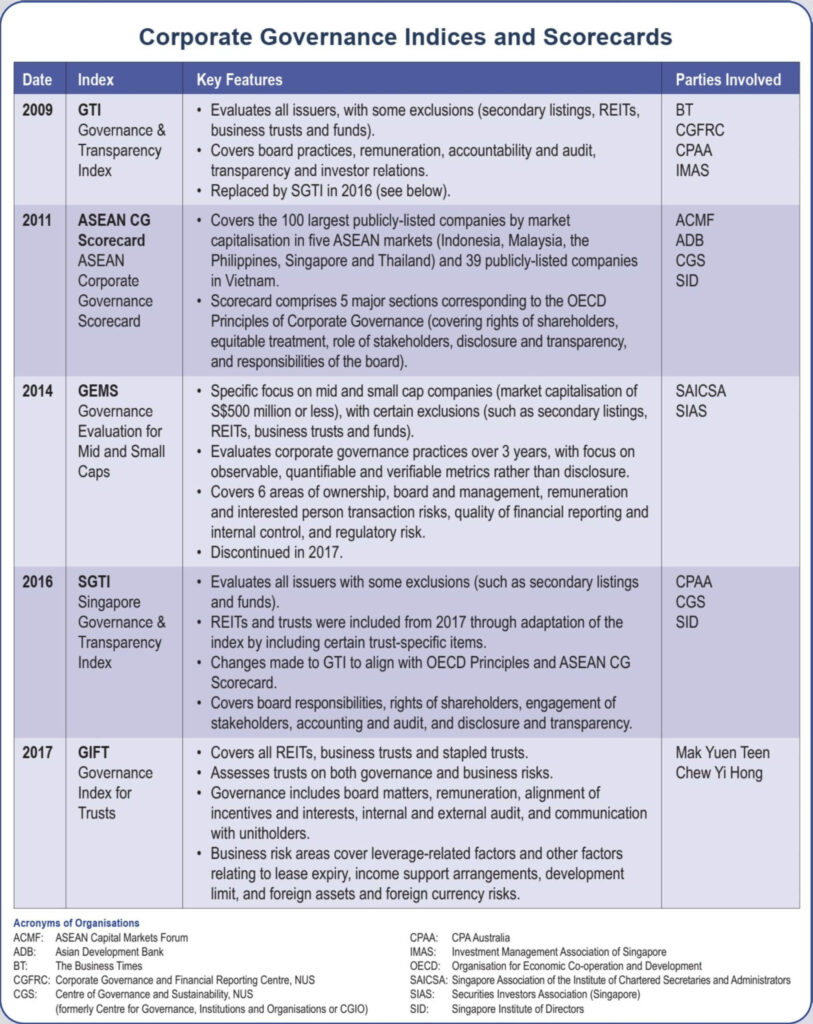

In addition to regulatory reforms, several corporate governance indices and scorecards were introduced by industry associations and academic institutions to raise awareness of and improve the standards of corporate governance.

The first was the Governance Transparency Index (GTI) which covered all listed companies (with some exclusions) in 2009. This later morphed into the Singapore Governance Transparency Index (SGTI) in 2016 with changes to align it to the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance in addition to Singapore’s Code.

In 2011, six ASEAN countries got together to create a pan-ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard based on the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance.

Meanwhile, niche indices such as the Governance Evaluation for Mid and Small Caps (GEMS) and Governance Index for Trusts (GIFT) were created in 2014 and 2017 for the small and medium sized enterprise and REIT sectors, respectively. The box, “Corporate Governance Indices and Scorecards”, describes these initiatives.

What next?

Since the last Code revision in 2018, there have been further initiatives to raise standards in areas such as board diversity and climate reporting. Some rules have proven hard to change.

For example, on the issue of multiple directorships, Singapore has vacillated and never reached a decision on a limit. Meanwhile, other Asian markets, such as South Korea, India, Malaysia, Taiwan and Vietnam, have introduced mandatory limits on the number of directorships a listed director should have.

With so few directors here having more than the five or six directorships that are commonly used as the limit (by some boards), why are we reluctant to do so at the national level? It is one thing to stand firm based on sound principles but another to keep sailing against the wind and ignore the real concerns of “overboarding”. Glass Lewis and Institutional Shareholder Services, the two largest proxy advisers in the world, have set limits of five and six, respectively in their voting guidelines for Singapore, and the former has recommended that Singapore companies follow “regional bestpractice” in this area.

That said, it is not mere tweaking of rules that Singapore really needs. The substance of corporate governance still leaves much to be desired in many companies. This can be attributed to several factors.

First, Singapore did not significantly improve regulatory and private enforcement in moving from a merit-based to disclosure-based approach. For disclosures to be credible, there must be consequences for material disclosures which are inaccurate, false, misleading or not timely. Little is generally done when companies breach disclosure requirements, and shareholders do not have the resources to pursue actions against issuers. Related to this is the lack of effective enforcement for breach of duties and rules by directors. There are signs that regulatory enforcement is improving, but it remains to be seen if it can be sustained, and whether accessibility to private actions will improve. Enabling class action lawsuits with funding schemes in Singapore could create alternative recourse for aggrieved minority shareholders.

Second, the “comply or explain” approach has not fulfilled its promise because the Singapore market lacks the necessary ecosystem for it to work. This approach may be effective for issuers that aspire to improve corporate governance but is ineffective for those that set out to harm minority investors and other stakeholders. Domestic institutional investors have generally been a disappointment.

Third, issuers listed here are highly diverse, and Singapore’s regulatory approach to corporate governance is not sufficiently risk-calibrated. Corporate governance risks are different for companies with different ownership structures, and foreign issuers compared to domestic issuers. For instance, the risk of expropriation of minority investors through excessive remuneration and interested person transactions is likely greater for family and founder-controlled and managed companies than for more widely-held and professionally managed ones. Resources are also different for large, mid and small cap companies. A taxonomy approach to corporate governance rules for different types of issuers should be considered.

Finally, 15 years after its establishment, Catalist urgently needs review and re-invention. In my view, the sponsor-based regime imported from AIM in the UK is not working. Catalist is filled with problematic companies. It is time to consider whether Catalist companies should be subjected to different rules focusing on the most critical corporate governance areas. Currently, Catalist companies comply with more liberal listing requirements in several areas, which create additional corporate governance risks.

A recent survey in the UK found that 89 per cent of AIM companies follow the Quoted Companies Alliance Corporate Governance Code, with only 6 per cent following the UK Corporate Governance Code, and the remaining 5 per cent following another Code.

However, it should not be “Code-light” for Catalist and smaller companies but rather “Coderight” for different types of companies.

About the Author:

Mak Yuen Teen is Professor (Practice) of Accounting at the NUS Business School. He has been heavily involved in the corporate governance scene in Singapore for the last two decades. He served on the committees that developed the first, second, and fourth editions of the Code of Corporate Governance in 2001, 2005 and 2018. He was involved in the development of several corporate governance indices and scorecards, and has served on various corporate governance award committees. He is a member of the Corporate Governance Advisory Committee under MAS, since 2018.

This article was first published in the Q3 2022 issue of the SID Directors Bulletin by the Singapore Institute of Directors.